October 1, 2018

Log-Jam: The Great Railway Transportation Crisis of 1917-1918

This is a story of how, in a national emergency, Big Government can do Big Things like no one else can.

In August 1914, after a century of relative peace, Europe suddenly erupted in a war that engulfed the continent. National rivalries, entangling alliances, and diplomatic blundering all played a part in the catastrophe. Great Britain, France, Russia, and Italy—the Allies—were locked in mortal combat against the Central Powers—Imperial Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey. Because the warring nations had overseas colonies, the conflict soon spread worldwide, and so it was called The Great War.

The United States, separated by an ocean from Europe, declared its neutrality. President Woodrow Wilson hoped to keep America out of the conflict. We were “too proud to fight,” he told his countrymen. But three years later, Germany’s repeated sinking of American ships and the discovery of a German plot to persuade Mexico to invade the United States combined to force Wilson’s hand. On April 2, 1917, he went before Congress to ask for a declaration of war against Germany and its allies.

The United States was unprepared for a major land war. The Navy might be the third most powerful in the world, but the Regular Army numbered only 100,000 men, a fraction of the size of European armies. Full mobilization would take time. In the first weeks following the declaration of war, citizens were asked to donate horses, guns and ammunition to the government. A military draft was instituted, and training camps were organized to train an army of millions of men. (1)

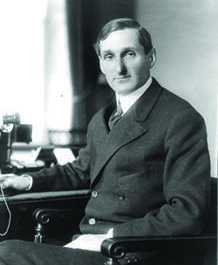

America’s chief weapons were its industrial might and its capacity to grow food. Britain, France, and Italy placed huge orders with American suppliers for ammunition, weapons, and other military equipment. The Allies also depended on American food production to feed their populations. The war years saw bumper harvests of grain and corn in the U.S., but the staggering increase in industrial and agricultural exports led to steep inflation and shortages. In such circumstances, a central authority was needed to regulate crop prices and guarantee an adequate supply of agricultural products for both domestic and overseas consumption. In August, 1917, the government established the U.S. Food Administration and appointed Herbert Clark Hoover as its chief.

A successful mining engineer and consultant, Herbert Hoover had earned a reputation for getting things done. At the start of the European war in 1914, Hoover in a private capacity had directed food relief efforts for starving Belgian civilians after the German Army invaded Belgium. Hoover was a blunt, humorless, no-nonsense administrator. As the nation’s Food Czar, he was given broad powers to act. He established price controls to stabilize the agricultural market and set production quotas. Coining the slogan, “Food Will Win the War”, he recruited thousands of citizens to go out and educate the public on self-rationing: “Meatless Mondays,” and “Wheatless Wednesdays”. Hoover set the example himself by being seen to place noticeably less food on his lunch plate than his colleagues.(2)

Hoover’s greatest task was to insure that at least a million tons of food were shipped to the Allies each month, or risk the war being lost. (3). This placed an enormous demand on the railroads to move agricultural products from growing regions in the Midwest and West to East Coast ports.

The War Department had its priorities, too: shipping construction materials for Army training camps and moving troops and equipment to embarkation ports. And there was the normal need for trains to haul freight and passengers.

Everything depended on the national rail system being able to handle this huge increase in traffic—yet American railroads were generally in poor shape financially and operationally to do so. In the Fall of 1917, a rail transport crisis seemed imminent.

A sixth of the nation’s railroads were in receivership; the Interstate Commerce Commission had refused repeated requests by railroads for rate increases; there was labor unrest over wages and conditions; skilled workers were being drafted or were leaving for better pay in other industries. After years of falling revenues, the railroads had not invested in expanded yard trackage, new rolling stock, or adequate repair facilities. And since many of the bigger railroads competed with each other, there was no effective pooling of resources to handle peak loads. The result was mass confusion: traffic jams and car shortages in the interior—while thousands of box cars sat at East Coast docks, waiting to be unloaded, but with nothing profitable to carry back home. (4)

By late 1917, congestion in freight yards, terminals and ports had gotten so bad that the rail transport system east of Chicago was in danger of a complete colapse. A shortage of 158,000 cars exposed New England to a winter without enough heating coal, and ships in port without fuel to cross the Atlantic. Something drastic had to be done. (5)

On December 28, 1917, Woodrow Wilson, by presidential proclamation, took the unprecedented step of nationalizing the entire U.S. railroad system as a temporary wartime measure. Never before in American history had the government taken over an entire industry, but as with the food supply, the national interest required a centralized co-ordination of transport. Under federal ownership, the railroad companies would be paid rent for the use of their equipment, repair shops, and tracks. Overnight, some 2,000,000 railway workers became government employees. When the war ended, the rail lines would be returned to their owners and compensation paid for loss and damage.

To head the newly-created U.S. Railroad Administration, Wilson appointed his son-in-law, the Secretary of the Treasury, William G. McAdoo, to be Director General of Railroads. McAdoo, a former corporate lawyer, had shown real executive capacity as head of the Treasury Department. In 1913, he organized the newly-created Federal Reserve banking system. In August, 1914, when war broke out in Europe, “Mac,” as he was known in Washington, closed the New York Stock Exchange for several months to prevent a run on the U.S. gold supply by panicky European investors. More recently he had organized the Liberty Loan bond drives, which raised millions of dollars to help pay for the war effort.(6)

McAdoo had to first relieve East Coast rail congestion, get the trains moving smoothly so food, war supplies and troops could reach their destinations. For closer control, all the railroads were organized into three Divisions: East, West and South. Civilian rail passenger service was cut back. Equipment, manpower, and repair services were shared between formerly competing rail lines.

Then came a crippling blow. In January, 1918, the worst winter in living memory brought ten weeks of blizzards, fifteen-foot drifts, and below-zero temperatures. The cold was so intense that when a freight train stopped to take on water or coal, its wheels could freeze to the rails. Four or five extra locomotives would be needed to help break the grip of the ice. Coal in open hopper cars froze solidly and had to be brought indoors to thaw. Repair crews worked double shifts in ancient, unheated roundhouses to repair burst steam pipes and cracked cylinders. (8)

By February, the slowdown in train movements from bad-order locomotives, traffic congestion, and snow-blocked tracks created a series of new crises for McAdoo’s Railroad Administration. Some 20,000 loaded freight cars were backed up between the Missouri River and Chicago. Food Administrator Hoover used the New York TIMES to warn that the next sixty days “would be the most critical period in the food history of the nation and the countries allied with it” in the war. Much of the U.S. corn crop (a record harvest) would soon spoil if it was not moved promptly to drying terminals. Grain elevators in the West could not get their bounty shipped for want of railcars. Most ominously for the war effort, Hoover noted that shipments of foodstuffs to Britain, France and Italy had fallen 50% below their monthly quotas. (9)

To underscore this last point, representatives of the Allied nations arrived in Washington to warn Wilson and McAdoo that unless the promised food shipments were restored, Germany would win the war. (10)

Using his full authority as Director General, McAdoo placed an embargo on all east-bound rail shipments except coal, food export, munitions and other war equipment. By his order, six trains a day left Chicago’s meat-packing districts with beef and pork for overseas shipment. Empty box cars from every part of the country were rushed to western grain states. “Solid trains” of a single essential commodity were given special departure days and a clear track all the way east. Southern and Gulf Coast ports were utilized to take up the overflow of export shipments. Officers and workers of the USRA and the railroads worked day and night during these critical weeks in February and March of 1918. (11)

By March 15th, 1918, a miracle had been wrought. The crisis had eased, helped by a spring thaw and the concerted effort of government and railroads. Allied merchant ships, their holds filled with American supplies, were on their way to Europe. There were more than 6,300 carloads of grain at New York and other Atlantic ports, waiting for ships.

The alleviation of the railroad bottleneck in the Spring of 1918 was a turning point in the war. The war ended on November 11, 1918, and William G. McAdoo returned to private life. When it became known that he had retired, and how small a salary he had taken during the war, grateful railroad workers around the country sent him telegrams and letters, thanking him for increasing their wages and for his services to the railroads. On March 1st, 1920, the U.S. Railroad Administration ended its existence by turning the railroads back to their owners and settling claims for loss and damage to equipment and track. In just over two years, the USRA had increased the efficiency of railroad operations, had modernized the railroad’s rolling stock and physical plant, and had saved the industry from complete collapse. (12)

Herbert Hoover’s U.S. Food Administration ended its official existence with the end of the war, but it gained a new name and new mission as the American Relief Administration, again led by Hoover; this time to feed starving civilians in war-torn Europe. In 1928, Hoover was elected President of the United States, but he had the misfortune to preside over the opening years of the Great Depression. In spite of all his previous achievements, he was unable to rescue the collapsed economy and was blamed for it, He has since come to be recognized as a great humanitarian.

Both William McAdoo and Herbert Hoover represented government officials who saw the big picture in a national crisis. They knew how to cut red tape. Working together, and harnessing the good will and talents of an entire industry, they helped speed the end of World War One.

Copyright © 2018, Aldon Company, Inc.

Reference Notes for “LOG-JAM, The Great Railway Transportation Crisis of 1917-1918”

- “Crowded Years, the Reminiscences of William G. McAdoo,” Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New

York, p 20 - a) Ibid. p.483 b) U.S. Food Administration,” Wikipedia, 5-19-2018 c) “An Uncommon Man, the Triumph of Herbert Hoover,” Richard Norton Smith, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1984, pp 79-80

- “Crowded Years,” op. cit. p. 483

- a) “The Railroad Builders, a Chronicle of the Welding of the States,” John Moody, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn., 1921, pp 125-127 b) “Crowded Years,” op. cit. p. 455 c) “William G. McAdoo’s Testimony Before the Senate Committee,” (Committee on Public Information), 1918, pp 118-119. (Google Digitized) d) “Crowded Years,”op cit., p. 451

- a) “U.S. Railroad Administration,” Wikipedia, (10-25-2016) b) “Crowded Years,”op. cit., p.457 b) “Crowded Years,” op. cit., p. 500

- a) “William G. McAdoo,” Wikipedia, (12-27-2016) b) “Crowded Years,” op. cit., p. 500

- a) “Crowded Years,” op. cit., pp 45, 463 b) “William G. McAdoo,” Wikipedia, (12-27-2016)

- a) “Cold Weather Again Hampers Railroads,” New York TIMES, 2-3-1918, Pro-Quest Historical Newspapers b) “The Work of the Division of Operation,” (US Railroad Administration), 1918, William G. McAdoo.(Google Digitized)

- a) Ibid. b) “East to Blame for Food and Fuel Shortage,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 2-6-1918, Pro-Quest Historical Newspapers. c) “Railway Review,” 3-2-1918, p. 292 d) “The Railroad Builders,” op. cit., p. 128 e) “‘Sixty-Day Crisis in Food Faces Us’ asserts Hoover.” New York TIMES, 2-22-1918, Pro-Quest Historical Newspapers.

- “The Railroad Builders,” op. cit., p.128

- a) Ibid., pp 119,128 b) “Railway Review,” 3-2-1918 c) “East to Blame for Food and Fuel Shortage,” op. cit.

- a) “Crowded Years,” op. cit., p. 487 b) “The Railroad Builders,” op. cit., p. 127

IMAGE CREDITS

- Wikipedia. Public Domain

- www.loc.gov/item/HEC2008007464

- www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004681933/

- www.loc.gov/item/96515511

- Dave Uphoff: www.minoktalk.com

Special thanks for photo research to Ginger Frere, at Information Diggers, and to Little Fort Media.